Photo by Lerone Pieters on Unsplash

Nikhil Chandra Nath

University of New Haven

One of the most prevalent cybercrimes in the era of digital society is identity theft, which affects individuals, businesses, and government. According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), in 2021, over 1.4 million cases of identity theft were documented in the United States, which is a 113% increase from 2019 (FTC, 2021). This increase suggests that technological advancements created opportunities for cybercriminals to steal and use personal information. Frauds have become more sophisticated, shifting from physical document theft to digital approaches like phishing, synthetic identities, and significant ransomware attacks (Haber & Rolls, 2024). Identity theft has serious consequences beyond financial loss. For victims, emotional and psychological harm is common, such as anxiety, stress, and reputational damage (Maher & Hayes, 2024). Fraud victims remain engaged for an average of over 15 hours spent resolving problems tied to fraudulent activity (Buzzard & Kitten, 2021). However, the issue is further complicated because many victims do not know how their information was obtained, making it harder for them to take adequate preventive actions.

New technology has both increased the risk of identity theft and provided potential solutions. Tools such as multifactor authentication (MFA), blockchain technologies, and biometric systems all promise to improve security, but these cannot be universally accessed (Almadani et al., 2023). For instance, small businesses have huge problems with the expenses for deploying decent cybersecurity systems; thus, cybercriminals can abuse them, taking the chance of vulnerabilities (Irvin-Erickson, 2023). Additionally, identity theft techniques are becoming more sophisticated, with AI-driven phishing schemes and deepfake technologies, which have created threats to existing preventive measures (Fakhouri et al., 2024).

Socioeconomic and demographic factors, creating disparities in victimization, are other critical contemporary issues for identity theft. In 2021, individuals aged 20−39 years were the most targeted, as they are the most active users of digital platforms (FTC, 2021). By contrast, older adults were less frequently targeted, but they suffered the most significant financial losses, costing an average of $9,000 per incident (Buzzard & Kitten, 2021). These disparities underscore the need to adapt preventive strategies and policies to specific vulnerability groups. Apart from personal risk, systemic issues like cross-border cybercrime and inadequate regulatory frameworks facilitate identity theft. Global data breaches, such as the Marriott breach in 2018, which disclosed 383 million individual’s personal information (Hu et al., 2023), illustrate how these problems are interconnected. To address these issues, public and private cooperation is needed, along with policy formation that helps to balance security and rights to privacy.

The aim of this paper is to critically analyze identity theft in the digital age through greater understanding of the technological advancements. This paper will examine the demographic and behavioral risk factors of identity theft, including age, sex, income, immigration status, online shopping, and social media visibility. This study will also evaluate how effective the existing preventive measures (document shredding, frequent password changes, monitoring credit, multifactor authentication, biometric systems, and software updates) are in countering identity theft. Through the literature review and examining three recent studies, this paper will analyze current policies and practices and their effectiveness in the era of AI-driven theft and deepfake technology. Additionally, this paper will discuss potential solutions, such as cross-border and combined initiatives, decentralization of data, and investment in proactive measures. Finally, it will suggest future investigations examining the methodological gaps to combat the increasing threat of identity theft.

Literature Review

Due to technological advancements, identity theft moved from the simple form (physical theft, dumpster diving) to the complex form of theft (phishing, ransomware, synthetic identity fraud). Allison and colleagues (2005) defined traditional identity theft as referring to physical theft of sensitive information, while Hu and colleagues (2023) referred to the use of digital schemes as modern identity theft. The latter include unauthorized use of credit cards, fraudulent account openings, and giant data breaches enabled by hi-tech hacking skills. One example is the Equifax breach that leaked personal data, like names, Social Security numbers, and financial information of 145 million people (Cowley & Eavis, 2019).

In 2016, victims of identity theft lost $24.7 billion in the United States, more than the $15.6 billion lost to burglary, motor vehicle theft, and other property crimes that year (Harrell, 2019; FBI, 2016). Apart from financial loss, 30% of victims suffered from moderate to severe emotional distress due to identity theft (Golladay & Holtfreter, 2016). This shows that identity theft can result in more than financial injury to victims. Nevertheless, 93% of victims did not report their cases to the police (Harrell, 2019).

Behavioral and Demographic Risk Factors

The risk of identity theft is influenced greatly by demographic and behavioral factors. According to Anderson (2006) and Harrell (2019), people with higher incomes, higher education, and more frequent online activities are at the highest risk. In particular, Harrell (2019) reported that individuals whose income is around $75,000 annually had a higher probability of facing identity theft than individuals with incomes less than $25,000. Furthermore, nearly 42% of identity theft victims were frequent online shoppers, which proves how digital appearance facilitates identity theft (Holtfreter et al., 2015).

Findings about gender and racial disparities are mixed, however. Allison and colleagues (2005) reported higher victimization rates among males, whereas Reyns (2013) mentioned that women and minorities were over-victimized. Behavioral patterns, including excessive social media use, frequent online shopping, and risky behaviors such as downloading from unverified sources facilitate the risks. Harrell (2021) reported that individuals performing high-risk online behaviors were 37% more likely to be identity theft victims. Interestingly, those who believe they are at a higher risk of victimization are often previous victims, perhaps due to increases in ongoing exposure from the past (Reisig et al., 2009). Although findings highlight individual risks, the systemic vulnerabilities including organizational weakness in cybersecurity infrastructure or national responsibilities of data breaches are often ignored.

Preventive Measures and Their Effectiveness

Many of the recommended preventive strategies for combating identity theft have been inconsistently effective. For example, document shredding is very efficient, which reduces the risk of stealing physically sensitive information (Burnes et al., 2017). However, digital preventative techniques, from frequently changing passwords to monitoring one’s credit, often fail to prevent fraud. According to Hu et al. (2023), 25% of credit monitoring subscribers had already been the victim of identity theft before they subscribed, further evidence that such services are primarily reactive, rather than preventive (Kahn & Roberds, 2008).

Monitoring bank statements or buying identity protection services can keep people safe from some of the impacts. However, these approaches were criticized by Leukfeldt (2014) and Reyns and Henson (2016) because they provide a false sense of security, generally not addressing the core vulnerabilities (such as systemic data breaches). For example, Harrell (2021) depicted that only about 70% of identity theft victims knew how their information was obtained. Thus, these reactive methods alone were not sufficient. In the same way, preventive measures through software can only be taken when they are updated constantly. However, over 40% of users ignore updating software (Mathur et al., 2018), thereby increasing their risk.

Multifactor authentication (MFA) and biometric systems, including facial recognition, are emerging technologies that can help to curtail risks to identity theft. Research indicated that MFA could protect unauthorized account access by 99.99% (Meyer et al., 2023). There are still challenges in the adoption of MFA by small businesses, along with affordability barriers for low-income individuals. Additionally, existing methods become ineffective faster with the changes in identity theft patterns and the employment of AI-driven phishing and deepfake techniques.

Regulatory Measures

Though policymakers and institutions have addressed identity theft in many ways, existing frameworks have encountered challenges in enforcement. In the U.S., there are specific mandated data protection measures like the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act (FACTA) and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA)). Although these regulations have resulted in an increase in accountability, 60% of the surveyed small businesses feel they do not have enough resources to be compliant with the broader system (Cowley & Eavis, 2019). Identity theft is global, and cyber criminals typically are based across geographical jurisdictions. According to Irvin-Erickson (2023), competing international laws and geopolitical barriers made it difficult to fight cross-border crimes. Moreover, financial institutions and private entities (such as credit bureaus) also have a vital but unexamined role in identity theft mitigation. Clearer regulatory guidelines are needed for how they can protect consumer data, and how they can address systemic vulnerabilities. Interestingly, Equifax had to pay $575 million in fines for a 2017 breach, emphasizing the financial and reputational repercussions of poor security (FTC, 2019). More recently, privacy debates arose regarding the improvement of data security. For instance, advanced surveillance tools for suspicious activities are also used to breach individual privacy rights (Leukfeldt, 2014). This is why a balanced approach to data protection is required, considering both the security and liberties of the individual.

Identified Critical Gaps and Limitations

The existing literature indicates some gaps regarding identity theft. The vast majority of researchers agree that risk is shaped by demographic and behavioral factors that can be reduced by shredding and monitoring. Nevertheless, there is no consistent effectiveness of digital measures, such as credit monitoring and the development of adaptive mechanisms to combat threats like AI use and scams (Hu et al., 2023). Despite progress, these gaps are necessary to understand for facilitating further development. When it comes to corporate data breaches, research tends not to assess and integrate individual risk factors with systemic vulnerabilities. Additionally, due to the underrepresentation of marginal populations (including immigrants or low-income people), equity issues are often ignored. Methodological shortcomings, like overreliance on self-reported data, often make it hard to find the actual problems. Finally, vast advancements in AI and limited longitudinal studies make it difficult to adopt prevention strategies, which need to be addressed.

Contemporary Research

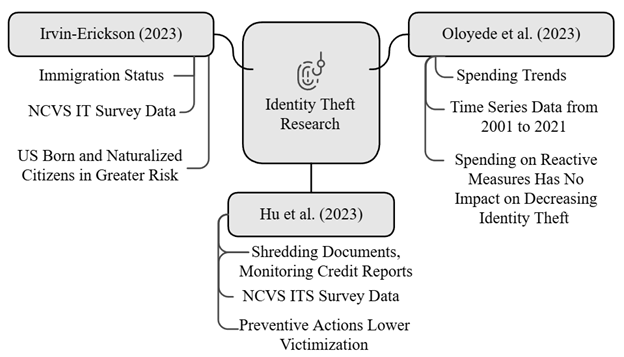

A recent study by Irvin-Erickson (2023) examined the effects of immigration status on victimization of identity theft using data from the 2018 Identity Theft Supplement of the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS IT). The data contained around 102,400 respondents aged 16 or older, obtained through a stratified multistage cluster design to achieve a sample of U.S. residents across various demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. The study grounded immigration status as a structural factor that influences social, economic, and digital visibility and, therefore, the vulnerability to identity theft, based on routine activities theory (Cohen & Felson, 1979) and lifestyle-exposure theory (Hindelang et al., 1978). It hypothesized that U.S.-born and naturalized citizens are at higher risk, because their engagements with digital and financial systems are high, while having ambiguous immigration status produces less exposure to such dangers (Figure 1).

Using logistic regression models, the relationship between immigration status and identity theft victimization were tested while controlling for demographic factors (e.g., age, gender, income, education), behavioral variables (e.g., online shopping frequency, prior data breaches), and protective behaviors (e.g., document shredding, credit monitoring). Interaction terms were included to determine how risk is influenced across immigration groups. To make the findings nationally representative, sampling weights were used, and additional Firth logistic regressions were conducted. The results supported the hypothesis that foreigners and descendants of foreigners had lower risks compared to US-born and naturalized citizens, who had greater financial and digital exposure (Irvin-Erickson, 2023).

The study revealed that both structural and behavioral influences produce statistically significant risk factors for identity theft. Victimization risk is directly related to the number of online transactions, whereby US-born citizens conduct an average of 50 transactions annually, more than any other group. Another key determinant is exposure to data breaches, with 14% of US-born individuals being exposed to breaches, as compared with lower exposure rates for other immigration groups. Greater risk was also correlated with demographic characteristics, including higher education and urban residency. Interestingly, as discussed earlier, the use of protective measures, such as identity theft services, significantly and positively correlated with victimization rates. Preventive actions, such as shredding documents, monitoring credit reports, or using identity theft protection services, also were evaluated in the study. Protection services are paradoxically related to greater victimization risk, while routine behaviors exhibited mixed effectiveness. Analyses of interactions showed that the effectiveness of these measures differs across demographic and behavioral groups, highlighting a need for prevention strategies tailored to systemic vulnerabilities of individuals.

Figure 1: Contemporary Research on Identity Theft

Oloyede and colleagues (2023) assessed identity theft in the United States Using time series data from 2001 to 2021 (Figure 1). This study used secondary data collected from Statista.com, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, and the Insurance Information Institute. Key variables from the dataset included annual consumer complaints about identity theft and total spending on cybersecurity in the public and private sectors. Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were used to analyze trends and relationships.

The descriptive analysis explored the trends of identity theft complaints and cybersecurity spending by depicting this growth during a two-decade period using graphical methods. Cybersecurity spending almost doubled between 2010 ($27.4 billion) and 2018 ($49 billion), while identity theft complaints increased from about 250,000 in 2008 to about 1.5 million in 2021. A chi-square analysis was performed to determine whether there was a relationship between the variables. No statistically significant relationship was found between spending more on cybersecurity and fewer identity theft complaints (Figure 1). Time series data were also used to capture long-term patterns, helping to derive a broader understanding of evolving dynamics between cybersecurity measures and identity theft. Descriptive graphs allowed for the evaluation of the effectiveness of cybersecurity efforts over the two decades.

Oloyede and colleagues (2023) mainly focused on how cybersecurity spending relates to identity theft complaints rather than focusing on risk factors. However, some highlighted trends included an increase in complaints and in cyber security spending. Spending on cybersecurity has more than doubled, yet identity theft has still risen. The importance is again underlined in taking more directed preventive actions towards identity theft, encompassing better public awareness, stricter organizational policy, and intensified international collaboration (Oloyede et al., 2023)

In another empirical study, Hu and colleagues (2023) examined data gathered from the National Crime Victimization Survey Identity Theft Supplement (NCVS ITS). The data source consisted of over 220,000 respondents aged 16 and older and covered a representative and varied population in terms of age, gender, and geographic location collected in three waves in 2012, 2014, and 2016. To attain broad applicability and reliability for policy discussions targeting identity theft prevention, the study employed a stratified multistage cluster sampling design. The authors tested whether preventive actions (shredding documents, monitoring credit reports, and using credit protection services) would lower the likelihood of being victimized (Figure 1). Identity theft victimization was divided into misuse of existing accounts (e.g., credit card fraud) and misuse of personal information (e.g., social security numbers).

Data were analyzed through the use of logistic regression models assessing the relationship between preventive measures and victimization while focusing on demographic characteristics (age, gender, income) and behaviors (online shopping frequency). Hu and colleagues (2023) identified several key risk factors for identity theft. Those with a household income of over $75,000 were more likely to be a victim of identity theft due to having greater financial assets and a larger digital footprint. Additionally, risk also increased among those with more frequent online transactions. Although younger adults (20–39) were more often targeted, older adults faced more significant financial losses — often over $9,000 per incident. Long-term vulnerability was seen by prior victimization being a significant predictor of repeat theft.

Furthermore, victims were unaware in most of the cases in which they became the victims (Hu et al., 2023). This study also examined the effectiveness of preventive actions. Frequent password changes correlated with prior victimization while shredding documents lowered victimization by 15%. Early detection, such as credit monitoring, was much better than reactive measures but did not stop identity theft. Preventive actions had modest effects overall, demonstrating requirements for more systemic interventions.

Policy Implications

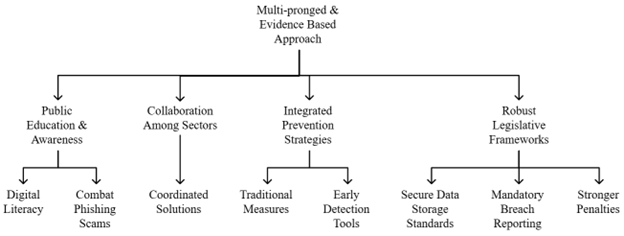

There needs to be a multi-pronged and evidence-based approach to addressing identity theft, drawing upon research evidence from different studies. Public education and awareness are compulsory to increase digital literacy and help combat phishing scams (Figure 2), along with the use of multifactor authentication (MFA), especially targeting high-risk populations like U.S.-born and U.S. naturalized citizens (Irvin Erickson, 2023; Piquero et al., 2020). According to the research, collaboration among sectors is important (Zachman, 1987; Figure 2). Coordinated solutions involving identity issuers, checkers, and protectors are required to secure data systems and materialize the potential of securing data systems from vulnerabilities (Wang et al., 2020). However, the implementation of advanced tools, such as biometrics, shared databases, and blockchain technology, to strengthen identity verification will need to harmonize among sectors (Newman & McNally, 2005).

Figure 2: Multi-pronged and Evidence-based Policy Implications

Integrated and proactive prevention strategies are also necessary. Traditional measures, such as document shredding, have consistently proven to be effective, according to Hu and colleagues (2023). Oloyede et al. (2023) pointed out the limitations of cybersecurity investment. Investment should now move on to tools that will assist early detection and the systemic resilience of evolving threats. Finally, legislative frameworks are needed to be robust (Figure 2). There must be standards for secure data storage, mandatory breach reporting, and more substantial penalties for violation (Figure 2). These measures together constitute a coherent strategy for dealing with identity theft.

Conclusions and Future Research

Identity theft has been a persistent and evolving challenge. Studies clarify its complex nature, including systemic, behavioral, and organizational issues. This paper discusses how emerging technology increases identity theft risk, and it provides ways to mitigate this risk using technology. Increased cybersecurity spending is demonstrated to be one of the current approaches to fighting identity theft. However, these efforts have had limited efficacy in reducing identity theft rates (Oloyede et al., 2023). Again, mitigation tools are more effective than traditional measures, such as credit monitoring and document shredding (Hu et al., 2023). Further targeted interventions are suggested due to the disparity in victimization risk between various demographic groups, particularly U.S.-born and naturalized citizens (Irvin-Erickson, 2023).

By providing a multi-dimensional analysis of the risk factors, preventive measures, and policy implications, this paper contributes to the discourse on identity theft. Additionally, this paper has reviewed insights from empirical studies on how individual behaviors interact with systemic vulnerabilities. It also highlights where technological and policy advances can have the most significant effects in alleviating demographic inequities and enhancing long-term resilience against identity theft. From these insights, both integrated prevention frameworks and emerging technologies need to be addressed in future research. For example, Blockchain and AI-driven approaches for detecting systemic fraud vulnerabilities appear promising (Kaur et al., 2024). Again, research should also be conducted among financial institutions, governments, and private organizations to examine the effectiveness of coordinated data protection strategies (Piquero et al., 2020). Research on digital literacy and other public education programs should be pervasive. Research on identity theft should include vulnerable groups, specifically older people who have encountered financial loss and who are visible on online platforms. These initiatives can help improve resilience against phishing scams and other cyber threats and protect personal identity (Patskanick et al., 2022).

In conclusion, this paper emphasizes an integrated approach while dealing with identity theft. These approaches involve the development of technology, inter-sector cooperation, and specialized public education based on demography. Bridging the gaps and providing actionable solutions through a literature review, this paper helps build a more resilient, secure digital space that protects individuals, companies, and institutions from the threat of identity theft.

References

Allison, S. F. H., Schuck, A. M., & Lersch, K. M. (2005). Exploring the crime of identity theft: Prevalence, clearance rates, and victim/offender characteristics. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.10.007

Almadani, M. S., Alotaibi, S., Alsobhi, H., Hussain, O. K., & Hussain, F. K. (2023). Blockchain-based multifactor authentication: A systematic literature review. Internet of Things, 23, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iot.2023.100844

Anderson, K. B. (2006). Who are the victims of identity theft? The effect of demographics. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(2), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.25.2.160

Burnes, D., Henderson, C. R., Sheppard, C., Zhao, R., Pillemer, K., & Lachs, M. S. (2017). Prevalence of financial fraud and scams among older adults in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 107(8), e13–e21. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303821

Buzzard, J., & Kitten, T. (2021). Identity fraud study: Shifting angles. Javelin. https://www.javelinstrategy.com/research/2021-identity-fraud-study-shifting-angles

Cowley, S., & Eavis, P. (2019, July 20). Equifax is said to be close to reaching deal in huge ’17 data breach. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/19/business/equifax-data-breach-settlement.html

Fakhouri, H. N., Alhadidi, B., Omar, K., Makhadmeh, S. N., Hamad, F., & Halalsheh, N. Z. (2024). AI-driven solutions for social engineering attacks: Detection, prevention, and response. Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR), IEEE, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCR61006.2024.10533010

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). (2016). Property crime. Crime in the U.S. 2016. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/topic-pages/property-crime

Federal Trade Commission (FTC). (2019). Equifax to pay $575 million as part of settlement with FTC, CFPB, and states related to 2017 data breach. Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2019/07/equifax-pay-575-million-part-settlement-ftc-cfpb-states-related-2017-data-breach

Federal Trade Commission (FTC). (2021). New data shows FTC received 2.8 million fraud reports from consumers in 2021. Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/02/new-data-shows-ftc-received-28-million-fraud-reports-consumers-2021-0

Golladay, K., & Holtfreter, K. (2016). The consequences of identity theft victimization: An examination of emotional and physical health outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2016.1177766

Haber, M. J., & Rolls, D. (2024). Identity attack vectors. In M. J. Haber & D. Rolls (Eds.), Identity attack vectors: Strategically designing and implementing identity security (2nd ed., pp. 109–118). Apress. https://doi.org/10.1007/979-8-8688-0233-1_11

Harrell, E. (2019). Victims of identity theft, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/vit16.pdf

Harrell, E. (2021). Victims of identity theft, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/vit18.pdf

Holtfreter, K., Reisig, M. D., Pratt, T. C., & Holtfreter, R. E. (2015). Risky remote purchasing and identity theft victimization among older Internet users. Psychology, Crime & Law, 21(7), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2015.1028545

Hu, X., Lee, J.-S., & Lovrich, N. P. (2023). Do commonly recommended preventive actions deter identity theft victimization? Findings from NCVS identity theft surveys. Journal of Crime and Justice, 46(2), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2022.2103015

Irvin-Erickson, Y. (2023). How does immigration status and citizenship affect identity theft victimization risk in the US? Insights from the 2018 National Crime Victimization Survey Identity Theft Supplement. Victims & Offenders, 18(7), 1401–1424. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2023.2231954

Kahn, C. M., & Roberds, W. (2008). Credit and identity theft. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55(2), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2007.08.001

Kaur, K., Venkatesh, R., Pundir, S., Brindha, S., Arul Mary Rexy, V., & Singh, R. (2024). Machine learning for fraud detection in blockchain transaction. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICKECS61492.2024.10616821

Leukfeldt, E. R. (2014). Phishing for suitable targets in the Netherlands: Routine activity theory and phishing victimization. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(8), 551-555. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0008

Maher, C. A., & Hayes, B. E. (2024). Nonfinancial consequences of identity theft revisited: Examining the association of out-of-pocket losses with physical or emotional distress and behavioral health. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 51(3), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548231223166

Mathur, A., Malkin, N., Harbach, M., Peer, E., & Egelman, S. (2018). Quantifying users’ beliefs about software updates. In Proceedings 2018 Workshop on Usable Security. Workshop on Usable Security, San Diego, CA. https://doi.org/10.14722/usec.2018.23036

Meyer, L. A., Romero, S., Bertoli, G., Burt, T., Weinert, A., & Ferres, J. L. (2023). How effective is multifactor authentication at deterring cyberattacks? arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.00945

Oloyede, A., Ajibade, I., Obunadike, Phillips, A., Shittu, O., Taiwo, E., & Kizor-Akaraiwe, S. (2023). A review of cybersecurity as an effective tool for fighting identity theft across the United States. International Journal on Cybernetics & Informatics, 12(5), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.5121/ijci.2023.120504

Patskanick, T., Ashebir, S., Miller, J., D’Ambrosio, L., & Coughlin, J. (2022). Financial fraud experiences at age 85+: An exploratory study with the MIT AgeLab 85+ lifestyle leaders panel. Innovation in Aging, 6(Supplement_1), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igac059.1180

Patskanick, T., Ashebir, S., Miller, J., D’Ambrosio, L., & Coughlin, J. (2022). FINANCIAL FRAUD EXPERIENCES AT AGE 85+: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY WITH THE MIT AGELAB 85+ LIFESTYLE LEADERS PANEL. Innovation in Aging, 6(Supplement_1), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igac059.1180

Piquero, N. L., Piquero, A. R., Gies, S., Green, B., Bobnis, A., & Velasquez, E. (2021). Preventing identity theft: Perspectives on technological solutions from industry insiders. Victims & Offenders, 16(3), 444–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2020.1826023

Reisig, M. D., Pratt, T. C., & Holtfreter, K. (2009). Perceived risk of Internet theft victimization: Examining the effects of social vulnerability and financial impulsivity. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(4), 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854808329405

Reyns, B. W. (2013). Online routines and identity theft victimization: Further expanding routine activity theory beyond direct-contact offenses. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 50(2), 216–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427811425539

Reyns, B. W., & Henson, B. (2016). The thief with a thousand faces and the victim with none: Identifying determinants for online identity theft victimization with routine activity theory. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(10), 1119–1139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15572861

Zachman, J. A. (1987). A framework for information systems architecture. IBM Systems Journal, 26(3), 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1147/sj.263.0276